LLVM Code Generation in HHVM

One of the most common questions we get about HHVM is why we don’t use LLVM for code generation. The primary reason has always been that while LLVM is great at optimizing C, C++, Objective-C, and other similar statically-typed languages, PHP is dynamically typed. The kinds of optimizations that provide huge performance benefits for static languages tend to be less useful in dynamic languages, or at least overshadowed by all the dynamic dispatching that’s done based on runtime types. We knew that there was probably something to be gained from using LLVM as a backend, but there were many larger opportunities go after first.

Warmup speed has also been a major factor in HHVM’s design from the very beginning, since we were replacing a compiled C++ binary with a JIT compiler. We needed to keep HHVM’s JIT pipeline as simple and as fast as possible to ensure that it could start up and serve web requests quickly enough to keep up with Facebook’s aggressive deployment schedule.

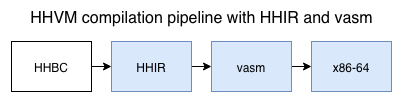

Once HHVM was in production and we had data indicating that we could afford to make the compilation process take longer in order to produce better code, we added an intermediate representation called HHIR between HHBC (our bytecode) and machine code. This new stage in the pipeline enabled all kinds of powerful, PHP-specific optimizations that we’ve been adding to for over two years now, nearly quadrupling the performance of HHVM in the process. A year after introducing HHIR we added vasm, a low-level IR positioned between HHIR and the final x86 machine code.

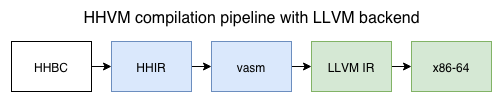

But there was still the question of what, if anything, an LLVM backend could buy us. About a year and a half ago, we started exploring this option in earnest. After considering a few options, we decided that we’d lower vasm to LLVM IR and then let LLVM handle final code generation, changing the pipeline to look like this:

We briefly considered lowering directly from HHIR to LLVM IR, since HHIR has more information about the source program than vasm does. It quickly became clear that the information lost while lowering HHIR to vasm was mostly PHP-specific metadata that LLVM doesn’t understand, so we decided that lowering from vasm would be fine. It would also be significantly less work, since HHIR is a much more complex IR than vasm.

After about a year of hard work, we got our LLVM backend up and running. The vast majority of the code is in the file vasm-llvm.cpp, but in terms of time and effort required to get the backend functional, that file represents a minority of the work put in. We had to make some fairly significant changes to HHVM, as well as a number of changes and additions to LLVM itself, for both performance and correctness.

Changes in HHVM

The modifications made to HHVM generally fit into two categories: reworking how HHVM’s JIT compiles PHP function calls and cleaning up some x86-specific concepts in vasm.

PHP function calls

The vasm instruction used to implement PHP function calls, bindcall, had some fairly odd semantics, for a variety of historical reasons. The primary consequence was that it wasn’t possible to spill live values to memory across a bindcall. HHVM uses different regions of memory for the PHP and C++ stacks, and keeps the PHP stack in a format that’s compatible with the bytecode interpreter. This means that when the JIT needs to spill temporary values, it uses the C++ stack. Rather than allowing each PHP frame to allocate whatever spill space it needed on the C++ stack, we used to allocate a fixed amount of space that was shared by all active call frames. In order to model bindcall as a normal LLVM invoke instruction, we removed this limitation so LLVM could allocate private spill space for the current PHP frame. This also helped our existing backend, since it could now keep values live across bindcall, rather than being forced to write all live values to their corresponding locations on the PHP stack.

Generalizing vasm

As mentioned above, vasm began life as a thin layer between HHIR and x86 machine code. As a result, vasm instructions were nearly 1:1 with the resulting x86 machine code. This included some x86 instructions with implicit inputs and/or outputs, like the idiv instruction. In order to cleanly handle instructions like this, we simply created new vasm instructions with explicit inputs and outputs. When translating vasm to LLVM IR, we handled these new instructions like any other instruction, but when translating vasm directly to x86 machine code, we first lowered the new instructions to their x86-specific counterpart. This allowed us to take full advantage of these x86 quirks in the default backend while also cleanly targeting LLVM IR. This work also helped pave the way for other, non-x86 backends in HHVM.

LLVM modifications

As of right now, our LLVM backend requires a modified build of LLVM. We added a number of features to support code introspection, code patching, and our custom ABI. We also modified some existing optimizations that were performing poorly on certain code patterns we frequently generate.

Location records

Location records, or locrecs for short, are a way for users of LLVM to get information about the specific machine instructions that result from LLVM instructions. We use this in HHVM for exception handling and certain types of state syncing, both of which have metadata tables keyed on the address of calls to C++ helpers. We briefly considered using stack maps to accomplish this, but according to the documentation, stack maps restrict certain optimizations and are a much larger hammer than we need. All we needed was the location of the code and none of the other features offered by stack maps, so we built the much more lightweight locrecs.

Smashable calls

Modifying code that may be running in another thread is a core part of HHVM’s design. We call this process “smashing”, to distinguish it from patching code that isn’t visible to other threads. The rules for doing this safely vary by platform, but on x86-64 the primary condition is that the entire instruction being smashed must fit on a single 64-byte cache line. This means that when we’re emitting a jmp or call that might be smashed, we ensure it does not cross a 64-byte boundary by inserting one or more nops before it.

LLVM didn’t support this particular type of alignment, so we added a smashable attribute for the LLVM call and invoke instructions. When this attribute is set, LLVM’s code generation backend will ensure that the call (or jmp, in the case of tail calls) is appropriately aligned for smashing. We then use a location record to get the final address of the smashable instruction, which is stored in our metadata tables.

As with location records, we considered using stack maps and patchpoints to implement smashable calls. Unfortunately, patchpoints don’t support our specific alignment constraints or tail calls, both of which are necessary for correctness in HHVM.

ABI issues

Our compilation units use a custom ABI that allows us to pass and return important values in specific registers. Luckily, it was easy to add a new calling convention to LLVM to support this, as well as another calling convention to support the way we call C++ helper functions.

A number of smaller tweaks to handle our unique stack and code alignment rules were necessary as well. Normal C++ functions on x86-64 expect the stack pointer to be 16-byte aligned before the call instruction, so they’re 8 bytes off of that alignment on entry to the function. The code emitted by HHVM expects the opposite: the stack pointer must be 16-byte aligned on entry. This allows us to call C++ helper functions without having to adjust the stack pointer first. We added the ability to specify a stack alignment skew value, representing how far off of the standard alignment the stack pointer will be coming into a function. As for code alignment, we added the ability to disable alignment of functions that don’t have the OptimizeForSize attribute set. We’ve done a number of experiments and found that, for our workload, the space lost by aligning functions is more of a performance regression than we could gain from aligning jump targets.

Performance tweaks

Finally, we changed a few of LLVM’s optimizations to better handle the code we throw at it. These were all opportunities we discovered by comparing the output of our custom backend with the LLVM backend. Some changes were enabling more uses of memory operands rather than explicit loads/stores (to keep code size down), and support for more compact conditional tail calls (performing a tail call directly with a jcc instruction, rather than a jcc to a call instruction).

Specific details about all of these modifications are available in our Github repository. We also maintain a patch that you can use to recreate our custom build of LLVM, until we finish upstreaming these changes.

Performance results

As measured by Perflab, our internal performance evaluation tool that replicates the same workload we see in production, the LLVM backend generates code that equals the performance of our custom backend. We spent some time comparing how the two backends did on specific pieces of code and found a number of situations where LLVM generated better code and a some where it generated worse code. Overall, the net effect was neutral.

Once reaching performance parity, we were able to prove that the LLVM backend was production-ready by deploying it to small groups of test machines for a day at a time. The extra compilation time introduced by inserting LLVM into our pipeline is quite large, but it can be mitigated by only using LLVM for the highest gear of our JIT, which is only used for the functions executed during an initial profiling phase.

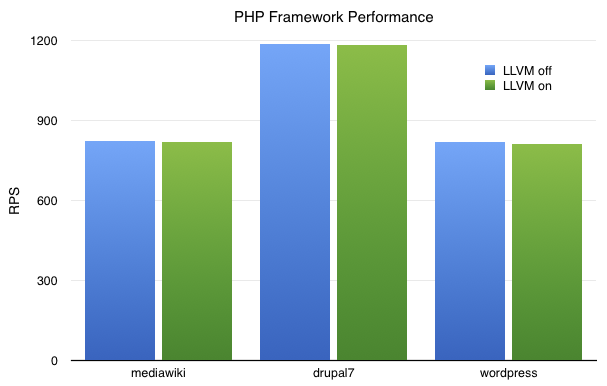

We also benchmarked the LLVM backend on some popular open source PHP frameworks using our oss-performance measurement tool. The chart below was obtained by averaging 10 runs each of MediaWiki, Drupal 7, and WordPress, using the runtime option -vEval.JitLLVM=1 to enable the LLVM backend. The y axis is requests completed per second at maximum load, so higher is better. The mean RPS with LLVM enabled is down about 0.5% for all three frameworks, though in all cases the difference between the two is smaller than their standard deviations. The raw data can be found here.

Ultimately, we decided to not deploy the LLVM backend to production for now. Making such a large change across the whole web fleet always comes with risk, and without a performance improvement to justify the risk it’s not worth it. We aren’t giving up, though–HHVM is still relatively young compared to other similar JITs, with plenty of room to grow in ways that may benefit the LLVM backend. We only recently implemented support for compiling loops within a single compilation unit, and as our HHIR optimizations become more sophisticated, the code we give to LLVM may start to look more and more like C code, which is what LLVM excels at optimizing. And JavaScriptCore has implemented their own LLVM backend with great results, which is very encouraging for the potential of using LLVM in a mature dynamic language JIT.

We’re not actively working on the LLVM backend right now, but we include it in all of our automated performance and correctness tests to ensure it doesn’t unexpectedly regress. And as always, anyone reading this who would like to take a look at what we’re doing and/or contribute can check out our Github repository!

Comments

- Bartosz Wójcik: What compilation options was used?

- Vivek: HHVM and Hack should participate in GSoC 2016, many students are interested to learn and contribute to this kind of challenging projects.

- Fernando: The result here was that using an LLVM backend did not yield any performance improvement, because LLVM is not capable of optimizing the kind of IR, that a JIT for a dynamic language tends to generate, well. The conclusion to draw from this is that HHVM is correctly focusing on implementing custom optimizations tailored to PHP on their own IR. This situation is the opposite of NIH. It's a case where a generic library (LLVM) fails in a specific situation (optimizing PHP) and one should use a custom implementation instead.

- Sendo desenvolvedor depois dos 40 - LF Bittencourt: […] da atualidade. O .NET CLR eventualmente vai interoperar com ele; o Mono já usa. O Facebook tentou integrar o LLVM com a HHVM e o WebKit migrou recentemente seu compilador JavaScript do LLVM para o novo JIT […]